My path from home to work.

Here medical students do not pre-round and

there are no patient presentations. I am

responsible for updating the physicians on any concerning lab results and am

expected to know the details of every patient’s management. At times I give a

brief summary of each patient, mostly to jog my attending’s memory. It is

somewhat like carrying all of the patients, with the exception that I don’t have

to make any formal presentations. I update any lab results from the previous

day, look over any new cases and wait for my attendings.

Lab results are in different units here,

which made for some hilarious moments in the beginning. A normal creatinine

here is 60-120. The first day I saw a patient with a creatinine of 75, I panicked,

convinced something horrible was happening to the patient. In addition there

are only paper charts, in the form of half page cards held together by staples,

glue and yarn. Each lab result is meticulously handwritten (in cursive and in French) into each chart, as well as all

treatment plans and discharge summaries.

I

work with two doctors: Dr. Justin Beyeme Omva and Dr. Fany S. Quenum. Dr. Justin is a Gabonese physician who has

been here for 16 years and has trained

countless American, Swiss and German students. Dr. Fany is a new addition to

the staff here. She studied medicine in Benin and recently completed a MPH in

Belgium.

We round on all 25-30 patients on our

service for several hours in the morning. Rounds here are very similar to the

states and consist of the nursing staff, the doctors and myself.

Our inpatient service is fascinating, and

the cases range from hypertensive crisis to HIV encephalopathy to TB. I made a list

of the cases one morning so you could have an idea of what we see on any given

day:

The chest film of the patient in room 4 .

1. Bacterial Meningitis, HIV

2. Stroke

3. Sickle Cell: Vaso-occulsive

Crisis, Osteonecrosis

4. Heart Failure

5. Metastatic Prostate Cancer

6. Gastroenteritis

7. Hepatic Abscess

8-14: Malaria patients

15. DKA

16. hypertensive crisis

17. tetanus

18. asthma exacerbation

19. angioedema

20. Pancreatitis (secondary to

ascaris lumbricoides infection)

20-26: Tuberculosis Patients

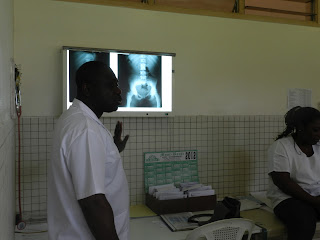

My attending, Dr. Justin sharing an interesting film with the team.

The film of the patient in Room 3

The film of the patient in Room 3

The inpatient ward itself is not very big. There are two patients per room and the nurses try to make each room unisex. There are four bathrooms with multiple stalls in the building and an outdoor area with charcoal for cooking and hanging washed clothing.

One

important difference about our inpatient service is the gardien system. Each

patient is admitted with a gardien or guardian, who is responsible for

preparing their meals, bathing them, taking their temperature and even dropping

off sputum samples. No one can be admitted to the inpatient service without a

gardien. This system dates back to the time when Dr. Schweitzer saw patients

alone with only his wife to serve as his nurse. He recognized that he could not

attend to the daily needs of each patient and called on family members to

assist in that regard. The system is still implemented today for the same

reason. There are only two-to-three nurses per service. They administer

medications, help turn and bathe patients and collect vitals.

Every so often the nurses walk down the

halls yelling for the gardien to do certain tasks.

“It is 8 o’clock,

put up the thermometers! It is time to take your patient’s temperatures.” or

“Rooms 1 and 2, you may use the showers now!” or

“Empty all urine bags into the vials!”

“Rooms 1 and 2, you may use the showers now!” or

“Empty all urine bags into the vials!”

At first I was taken aback by this system,

but now I must say I like it. Patient’s family’s are forced to be involved in

the care of their loved ones, and are able to observe their patient overnight.

They often have valuable insight into the state of their loved one’s condition.

It is especially useful in this setting because there are no established mechanisms

to provide home nursing. Families learn to care for their family members while

they are hospitalized under the watchful eye of the nurses and are then

continue that care at home.

The Rene Kopp building, the Inpatient Adult Medicine Service.

"Weigh all patients Monday, Wednesday and Friday. For the patients on Lasix,you must weigh them every day."

Often I forget that I am not in the states,

because some of the same basic discussions about patient care happen here:

“This patient needs to be rotated to

prevent the formation of decubitus ulcers (eschars).”

“We need to remove the urinary catheter (sonde) this afternoon.”

The outpatient clinic, or Polyclinique.

After rounds, I update the service’s registers, assist with discharge paperwork and tie up any loose ends. Then we head to the Polyclinique to see outpatients. On average we see 12-20 patients in the afternoons. I work with both attendings as well as a third physician Dr. Ulrich Davy Kombila in the afternoons, rotating each day. Dr. Kombila is a physician who works in the hospital as well as for the Research Unit here and works primarily on HIV and TB coninfection.

I feel that I am learning so much at the

polyclinique. There are many advantages to being the only student on service. I

examine each patient before my attending, relay my findings, then he/she

examines the patient after me, confirming or clarifying my findings.

Unfortunately by the time patients here seek medical attention, their illness has

progressed. However, this means that the physical exam findings here are

impressive. In one month, I have palpated more enlarged spleens and livers, auscultated

more murmurs, rubs, crackles, and stared at more rashes than I have in six

months in the states. I believe that my physical exam skills are benefitting

greatly from this experience.

One afternoon at the Polyclinique looked like

this.

1-4:

HIV followup visits

5-7. HTA/DM follow up

8. A case of loa loa

9. Otitis Externa

10-12: Three pregnancies, one set of

triplets (outpatient Ultrasounds for the maternity department)

13. A newly diagnosed HIV positive patient

14. A case of malaria(we admitted him)

15. Chlamydia

16. A case of tuberculosis

After we see all of

our patients around 1400/1500, we head to the dining hall. Then I am free to go

home. I come back to the hospital at 1700 to the laboratory to collect lab

results. Then I write them in the paper charts and call the night call physician

to notify them of any abnormal results.

At first, I was terrified by this task. I am

the first to see any lab results, xrays and ecg for every patient. My

attendings trust me to spot anything alarming. The first couple of nights I

reported every abnormal result, even if it were only several digits above or

below the norm. Over time, I have started to pick out the lab results or

findings that my attendings needed to know or that might change patient

management in some way. I am having to apply everything I learned about xrays

and ecgs. It is wonderful and terrifying.

My third week here, everything came full

circle for me. I was able to contribute to a patient’s care in a a small but important way:

A fifty year old man came to Polyclinique

complaining of severe abdominal pain. He stated that the pain had started a day

earlier after an episode of diarrhea. When we saw him, he was in unbearable

pain and could not sit still for the echo. His abdomen was hard and distended.

My attending saw some nonspecific changes which he thought might point to an

obstruction but insisted that we order a abdominal film to confirm.

After clinic ended, I decided to go strait

to the lab to pick up results. That day it looked like it might rain so I

figured if I got the results early, I would have less chance of getting stuck

in the daily afternoon rain storm.

Among the results were our patient’s

abdominal xray. I hung the film and looked at it. I am by no means a stellar

student when it comes to xray but I knew immediately that this was an

obstruction. Here is the film I saw:

Because I am the first to receive all

results, I called my attending and told him what I thought I was seeing. He told me he was on his way and would

call surgery. Then I asked the nurses if they had an NG tube, which we placed.

Our patient went to surgery that evening.

I called home that night and gushed to my

parents: “Mom, Dad, I saw this xray and I told my attending about it and the

patient got surgery! I read the life out of that film!” My parents, in their

usual fashion, were not quite sure why I was so excited but listened to my

hurried speech anyway. It was rewarding

to contribute to a patient’s care directly, to have to depend on the skills I

acquired at Wake and apply them to an actual case, and to have my input lead to

a resolution for a patient. It was a wonderful day.

No comments:

Post a Comment