The

music drifted through the hallways, past other patient rooms, and through the

nurses station. It became the background of our work and, after a time, even

the other patients were humming the tune. When we visited the patient in Room 25,

his guitar was always in his hands, his mask on his face at an angle. Ever the

artist, he wore the mask like an accessory, how a lead guitarist might wear

sunglasses or a hat.

The only times he was without his guitar were the times he was overcome by coughing fits. Then, the only sound we heard coming from his room were his harsh coughs.

Before

I came to Gabon, I read about tuberculosis. After reading the chapter in my

Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine, I formed an image in my mind of a patient

with tb. The patient I envisioned was much older than me, frail, ill and HIV +.

In my mind’s eye, their already compromised immune system had let the malicious

little mycobacterium set up shop in their lungs.

What I

found when I arrived, however, were mostly young patients, young enough to be

in my circle of friends. They were mostly HIV negative and led very active

lives that were only slowed by their disease.

The only times he was without his guitar were the times he was overcome by coughing fits. Then, the only sound we heard coming from his room were his harsh coughs.

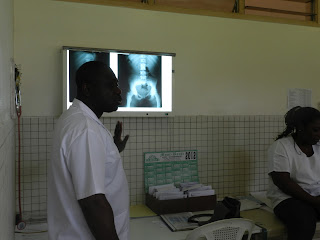

The chest xray of the patient in Room 25.

For this reason, the

mood in the tuberculous isolation ward is often light and youthful. The patients spend

ten days with us, just long enough for us to get to know them and long enough

for them to personalize their rooms. I remember two young men who were admitted

on the same day brought a card table and dominoes to their room. They were always playing and joking, enjoying

the break from college studies. In the afternoons, I could hear them playing,

the sound of dominoes slamming down on the table.

Although the mood in the isolation unit is often light, the tuberculosis problem in Gabon is serious, with an estimated national prevalence of 379/100,000. Unfortunately, the public health infrastructure in Gabon is ill-equipped to adequately address the issue. The WHO advises that all TB patients should have at least the first two months of therapy observed, in the form of a health official watching patients swallow their anti-TB therapy. However, the Albert Schweitzer Hospital is not adequately staffed to be able to fully apply the recommended Directly Observed Therapy or DOT, recommended by the WHO. Physicians are forced to rely on the cooperation of infected patients, a challenge when most of the patients are young and otherwise healthy.

They came to the outpatient

clinic with the same presentation:

“Docteur I cough until my chest hurts,”

they said, running their hands across their chest, from shoulder to

shoulder.

Or

“Sometimes I cough so much I feel I will throw up

everything in my stomach.”

Or

“I have fevers all the time and I wake up and all

of my bed sheets are wet.”

Or

“He has lost so much weight his clothes barely

fit,” from an anxious mother or aunt.

We

asked the three same questions to these patients: I heard it so many times, in the same order

and rhythm, that I turned it into my own song: Delivered in a singsongy voice

“Tu tous? Tu craches? Tu a la fievre?” Do you cough? To you spit? Do you have a

fever?”

When

they answered “Yes” to all three, we immediately get the ball rolling: Chest

Xray! Sputum Examination! HIV test! Admission to the Kopp!

Admission to the inpatient service is only the beginning of six month long treatment. The patient I saw today was a young woman who was recently released from the inpatient service after ten days of DOT. Her story sounded like dozens of others I have heard since I arrived. She came to the clinic complaining of a cough that made her chest ache, fevers and the constant sensation of being exhausted. Her CXR gave us the diagnosis,a perfectly defined cavitary lesion in the apex of her left lung.

Her chest xray.

She was admitted and submitted three consecutive days of sputum samples; all three were positive. (The gold standard diagnosis is a culture, but is not possible here due to lack of an appropriate laboratory facility. It is also impractical due to the time needed to culture mycobacterium).

Her mantoux (PPD skin test) was positive as well. She took RHZE (rifampin, isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide in a combo pill) and a pyridoxine pill for a total of ten days inpatient. On the ninth day of her hospitalization, we tested her liver transaminases (three of the four drugs in the combo pill, R, H and Z can cause drug-induced hepatitis), then sent her home with a follow up visit in one month and a month's supply of RHZE and pyridoxine.

Today, I thoroughly examined her and asked if she was tolerating the medication. Then she submitted a sputum sample. I made her another appointment in one month and gave her a month's supply of both medications. She has two more visits like this one as well as an xray and repeat liver transaminases at the end of her 6-month treatment.

It is a long process, and at each step, the physicians count on the patients to cooperate by taking the medication and coming to appointments. And, although the medications and appointments are free, patients are often lost to follow up. Studies looking at default rates in Subsaharan Africa have found that two of the most predictive indicators of default are age and gender. Young men, like our musically inclined patient in Room 25, have been found to be statistically more likely to not complete their treatment.

The chest film of a patient with pleural TB, one form of extrapulmonary TB. Patients with pleural tuberculosis have negative sputum and, for this reason, it is thought that they are not contagious. (We diagnosed this case after examining the pleural fluid: It was exudative with a lymphocyte predominance)

The day before we were planning to discharge the

patient in Room 25, our attending jokingly grabbed his guitar and pretend to

play, while he and the other patient laughed. It was a wonderful moment, one I will remember, long after I have left Lambarene.

I’m always a little sad to see them go; it is

like I am saying goodbye to a classmate. I am also scared for them.

My fears are not unfounded. A public health Schweitzer fellow, Meredith

Collins, completed a study about tuberculosis during her rotation here. She found that in 2008, 43.5% of tuberculosis

patients were lost to follow up. It is a problem all over subsaharan Africa, but the numbers are alarming.

When we discharge our patients, I always worry

that their youth and the feeling of invincibility that come with it will cause

them to forget their medications and miss appointments. I worry that the

morning they wake up without a cough and able to play soccer without tiring,

they will decide they don’t need to take the five pills. And most of all, I

worry that they will come back, their lungs filled with bugs that we don’t have

the medication to kill. In those moments, I feel so much older than them, the knowledge

of all the risks of their infection aging me.

I’m

never sad for long. After our guitarist left, another young man replaced him,

this one with a boombox and a seemingly endless collection of American

music. The sounds of Rihanna and Jay-Z

filled the hallway for the next couple of weeks, and by the time we discharged

him we had started to hum right along to it.